After looking at where the headline $4 billion figure came from previously, we now turn our attention to another big number that’s getting bandied about the place: $1.7 billion in over-payments that the Government wants to claw back.

This number comes from the 2015-16 Federal Budget. The Hockey/Cormann budget. The “lifters and leaners”, let’s go smoke cigars within view of the cameras budget. You know the one.

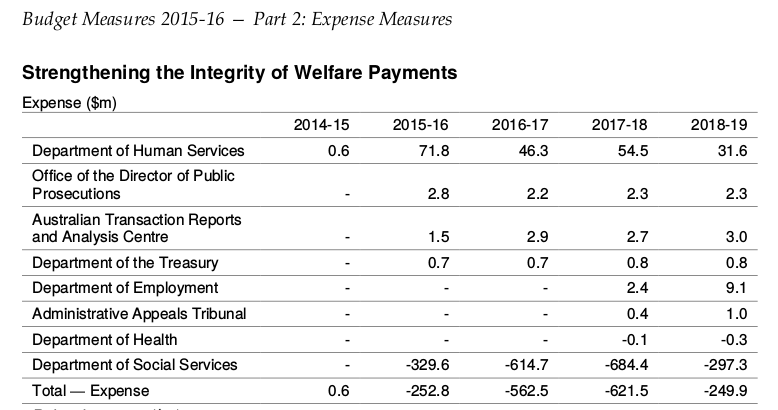

Anyhoo, on page 116 of Budget Paper No. 2 [PDF] we find this statement:

The Government will achieve savings of $1.7 billion over five years by enhancing the

Department of Human Services (DHS) fraud prevention and debt recovery capability,

and improving assessment processes.

From 1 July 2015 DHS will implement an integrated package of compliance and

process improvement initiatives including improved automation and targeted

strategies for fraud prevention in areas of high risk.

The savings from this measure will be redirected by the Government to repair the

Budget and fund policy priorities.

Just under this table:

The sum of that Total — Expense line over five years is $1,687 million, which rounds up to $1.7 billion. The actual amount the Government reckons will get clawed back is in that Department of Social Services line, a total of $1,926 million over five years.

Okay, how was that worked out? It’s not spelled out in the Budget, which is where Senate Estimates comes in, and questions asked of the Government about what this all means.

Improving Data Matching

The Budget was handed down on 12 May 2015, and a couple of weeks later, the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs asked some questions about it.

DHS has performed data matching of income data from the ATO for some time as part of its audit and risk management process, which is fair enough. It’s supposed to find fraud, as well as simple mistakes, so that DHS isn’t giving out taxpayer money to the wrong people.

The process had traditionally been pretty labour intensive, and only done a couple of times a year, because it took too long and cost too much to do it more often. Ms Kathryn Campbell, Department Secretary for DHS, told the committee “Using the newly developed streamlined intervention approach, the savings now far outweigh the cost of undertaking the activity and far outweigh the cost of the overall measure.” This new approach is the Welfare Payments Infrastructure Transformation (WPIT) Programme.

It’s worth reading Hansard for 3 June 2015 [PDF] to get a good idea of what the programme is really all about, starting on page 67. It’s about finding mismatches between what people have declared their income was to DHS, and what they declared to the ATO.

Senator CAMERON: This is just targeting welfare recipients basically?

Mr Withnell: Yes. It is a target on those welfare recipients who have underdeclared their

income.

Page 77 also provides some insight into the programme.

Mr Withnell: Probably the easiest way to describe it is that most of the strengthening

integrity in the welfare system measure deals with historic overpayments but also provides

some money for development into the future, which will connect into the welfare payment

infrastructure.

Senator SIEWERT: I am having trouble hearing you.

Mr Withnell: With the budget measure most of the savings are historic overpayments, so

they are overpayments that have already occurred. Those savings, in a sense, are retrospective

because they have already occurred. In terms of benefits going forward there is a small

amount of funding within the compliance measure which allows us to take advantage into the

future of the developments in the welfare payment infrastructure transformation program.

So it’s all about getting people to pay back money that DHS paid them already, but shouldn’t have because the information in the DHS systems wasn’t accurate, for one reason or another. At least, that’s the theory.

But here’s where things start to go wrong.

Numbers That Don’t Add Up

On page 78 of Hansard, we find that the Budget figures above are probably wrong.

Senator SIEWERT: And they all add up to $1.7 billion?

Ms Campbell: I have not got that.

Ms Golightly: No, the $1.7 is purely to do with the business integrity measure.

Senator SIEWERT: Which is the fraud?

Mr Withnell: It is both.

Ms Campbell: I think the net number is $1.5 billion, because it is $1.7 billion in savings

and $200 million in expenses, which is a net $1.5 billion.

In the Budget, we saw $1.9 billion become $1.7 billion after the $200 million in expenses to set the system up were taken out of the debt recovered. But here we discover that the revenue is actually $1.7 billion, so we end up with $1.5 billion after taking out the costs of settings things up.

Senator Cameron asked about the business case underlying this program. It was taken on notice (Question 15) and an answer was supplied on 24 July 2015 [PDF]. The answer show us how this $1.7 billion was worked out. I’ve summarised it in the following table.

| DHS analysis | Headline Version | Error | |

| Discrepancies with Debt (%) | 85.00% | 100.00% | 15.00% |

| Number of potential debts | 918,000 | 1,080,000 | 162,000 |

| Likely average debt value | $1,440 | $1,440 | |

| Predicted debt value ($’000s) | 1,321,920 | 1,555,200 | 233,280 |

| Additional recovery fee (10%) | 10.00% | 10.00% | |

| % of debt subject to recovery fee | 100.00% | 100.00% | |

| Recovery fee value ($’000s) | 132,192 | 155,520 | 23,328 |

| Total value estimated ($’000s) | 1,454,112 | 1,710,720 | 256,608 |

To explain, in the answer to Question 15, DHS explained that, based on their analysis, there were about 1,080,000 instances of a mismatch between what people had declared to Centrelink they’d earned, and what the ATO says they earned.

Of those, about 85% would result in a debt, with an average value of $1,440. If you use the “mismatches” instead of the reduced 85% figure, you get $1.55 billion, but the real amount should be $1.32 billion (more on this in a moment. Stay tuned, it’s a doozy.)

Recent legislation also adds a 10% debt recovery fee to this money, which bumps our wrong total to $1.7 billion. If we add it to our 85% based figure, we end up with $1.45 billion.

Take away the $200 million the project will allegedly cost, and we end up at $1.2 billion. Half a billion dollars gone because of some dodgy maths.

These amount will also need to be further discounted based on how recoverable they are. We’ve already seen a big write-down in the receivables on DSS’ balance sheet for these alleged debts, so the real number is even lower than this. The discounts to the real number certainly do add up, don’t they?

And this is the “business case” justifying the programme.

Underpayments

Note how there’s nothing in the answer to Question 15 about the other 15% of the mismatches? If they’re a mismatch with the ATO, that means the amounts are not the same, so the debt can’t be zero. Since 85% are overpayments, that means this 15% must be underpayments. But what’s their average value? That’s money DHS should be paying people, so the value of the debt should be discounted by this amount.

At least, that’s what DHS should be doing, if Ministers Tudge and Porter, and the DHS actually meant the “no less” part of the line they’ve been spouting for weeks.

Let’s pretend DHS were planning to pay people who got underpaid. How big a problem is it, really? Well, 15% of the discrepancies is 162,000. The discrepancy to customer ratio is about 1:0.8, so if we assume the 15% has roughly the same mapping of discrepancy:customer that’s 129,900 people the Government owes money.

Now, the average underpayment could be very different from the average overpayment, so we’re getting even further out into inaccurate figures now, but let’s assume the average per debt is the same: $1,400. That would mean DHS owes people over $233 million. If DHS actually paid people the money it owes them, the savings from this robo-debt fiasco would be reduced down to under $1 billion. A far cry from the $1.7 billion in the headlines, eh?

Of course, it isn’t being included, because DHS has no intention of paying anyone that money.

So much for the integrity of the system.

“there were about 1,080,000 instances of a mismatch between what people had declared to Centrelink they’d earned, and what the ATO says they earned.”

Isn’t this fundamentally broken if they are using annual ATO figures at this point and dividing by 26? Is the $1.X billion even real?

Well quite. Since they don’t know why the discrepancy exists (if they did, they wouldn’t need to send a bunch of letters), they’ve made some sort of assumption (based on what info we again don’t know) about how to figure out the likely debt amount.

If they’ve used the same “average ATO income over 26 fortnights” approach that is trivially, obviously wrong, then the whole “business case” is highly suspect, innit?

An enterprising Senator might like to pursue that line of questioning at an upcoming Estimates hearing.

Might also be worth mentioning that the 15% no-debt statistic is likely a best case scenario provided by DHS. The minister appeared to concede this was 20% which means it’s probably somewhere below 30%, or it was at that time.

After that, there’s the erroneous debt calculation percentage, which by most accounts, is in excess of 30%, as it was already prior to this program.

Then there’s the appealed debt ratio, relatively small, but a significant amount are overturned on appeal.

Then of course – there’s just the general ‘disputed’ debt which for these policies, so far, is not looking like a nice statistic for the Government. Indeed, they haven’t even released it. I doubt they will until they’re forced to. Even then, it’ll likely be fudged.

So at the end of the day they may be left with a few correctly calculated debts. But they have to pay collection fees and account for a standard non-recoverable rate percentage.

How much money is this going to make? Good work, keep digging :)

The 20% you’re referring to is “there is no debt” after the letters about discrepancies are sent, so that’s 20% of the 85% of discrepancies identified, so we’re down to 68% of the discrepancies maybe being a debt of some kind.

I’ve asked DHS for more info on what the debt amounts on the 80% of the letters actually pans out to be. Then we can see how realistic that $1440 average was, particularly since we’re talking about a substantially lower discrepancy amount.

The percentage referred to debt collectors was <10% of the total debts recovered in previous years, just as a data point. It's somewhere in the DSS or DHS annual reports. I'd look for it, but it's late and it's time I got some sleep.

While the Govt does have a legislated duty to recover fraudulent overpayments, ACOSS has noted that outright fraud detected in the Centrelink system has been “at the margins with 0.018 per cent of those receiving payments investigated for fraud last year with 996 cases referred to prosecutors and just 29 cases resulting in indictable charges.”

There are plans to introduce a new card (can’t find the reference right now – it was in a Govt paper) additional to the Cashless Welfare Card. Soon all Centrelink clients might as well wear a brand on their clothing.

I am outraged. Not only is data matching a logical error, it indicates a far greater problem at Centrelink in terms of administrative management.

These overpayments should not be happening, and if Centrelink overpays a client without the client being complicit in that, legislation states the overpayment is unrecoverable.

#NotMyDebt